There’s a common saying among musicians that you’ve got to learn the rules of music theory before you can break them. Yet some of the most famous pop songwriters couldn’t read sheet music or describe the logic behind their chord changes.

Paul McCartney famously explained in an interview on 60 Minutes that he relied on ear training, intuition, and experimentation to write songs for The Beatles. He wasn’t the kind of composer who relied on math and abstractions to write music.

That being said, the fundamentals of music can help you to build a shared vocabulary with other musicians. If you want to play jazz, you need to be able to read and interpret chord charts. You might be able to get by on pentatonic scales for a while, but high-quality improvisation and soloing will eventually call for a more nuanced understanding.

Studying classical music and jazz theory can be a kind of trap as well. Academics who get stuck in abstractions and theoretical frameworks tend to lose touch with the creative spirit of music. Knowledge without practice gets in the way of direct creative expression. So at the end of the day, as in all things, the balance is found somewhere in the middle.

This article will take you on a journey through the particularly sticky music theory topic called tritone substitutions. Let’s see if we can make it through to the other side together. We’ll start with the basics.

What is a tritone?

The tritone interval refers to the distance between two notes separated by six half-steps or three whole-steps. The word itself combines the prefix tri- (three) and tone, referring to the three whole-step intervals that exist between the two notes.

Tritones are a sonically complex and dissonant harmonic interval (45:32), compared to more common intervals like the octave (1:2), perfect fifth (2:3), and perfect fourth (3:4).

For centuries, the tritone interval was seen as taboo among Western church composers, earning the name diabolos en musica, or the devil in music.

Yet despite the stigma attached to the tritone, it occurs naturally in every diatonic scale. In the key of C Major and its relative key of A Minor, the tritone sits between the notes B and F.

What is a tritone substitution?

Tritone substitutions are a technique that swaps one type of chord for another. The trick became popular in bebop jazz tunes during the 1940s, as artists outgrew standard 12-bar blues and sought out more complex ways to express themselves. It’s remained a core part of jazz theory for guitarists and pianists to this day.

A tritone sub is most commonly achieved by replacing a dominant 7th chord with another dominant chord, located three whole steps above or below. The distance between those two root notes is the tritone interval, and the substitution refers to the replacement. Pretty simple, right?

See the diagram above for an example of sheet music notation. In the key of C Major, the G⁷ dominant chord is replaced with a C♯⁷ chord, which can also be spelled enharmonically as a D♭⁷ chord. Enharmonic refers to the fact that C♯ and D♭ are the same note, notated in two different ways.

Below is a second diagram showing the G⁷ and D♭⁷ relationship on a circle instead of sheet music. It might look complicated, but it’s not too bad. Let’s break it down one piece at a time.

- The purple shape connects with the notes G – B – D – F (G⁷). This is the original chord.

- The blue shape connects the notes D♭ – F – A♭ – B (D♭⁷). This is the tritone substitution.

- The green line labeled “tritone axis” shows the two notes that stay the same in both chords

- The solid red line shows the tritone interval between G and D♭

- The dotted red line shows the tritone interval between the two remaining notes

If the sheet music and circle diagram are still confusing you, hang tight because it might make more sense once we move to this next concrete example of how it works in a chord progression.

Use tritone substitutions in Hookpad!

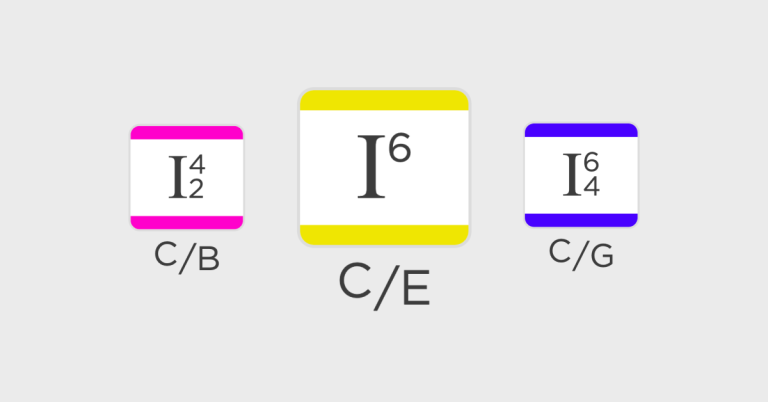

Modifying the standard ii-V-I chord progression

Let’s apply this knowledge to something any Jazz musician will be familiar with. In a ii → V → I progression, the dominant chord (V) is replaced, turning it into ii → ♭II⁷ → I progression.

- In the key of C Major, a standard ii → V → I would be Dm → G⁷ → C.

- With a tritone sub, the ii → ♭II⁷ → I progression is Dm → D♭⁷ → C.

Does that make a little more sense?

This transformation creates a unique tension and resolution thanks to the voice leading in the flattened second scale degree as it moves down to the root note.

Jazz musicians looking to improvise or write licks over a tritone sub generally use an altered scale or Lydian dominant scale, which is the fourth mode of the melodic minor scale.

Rather than dive super deep into solo improvisation techniques, we will stay broad and show you how tritone subs have been used across a broad variety of genres for over 70 years!

To make this even easier, we’ll share examples from TheoryTab, a free web app that lets you listen to each example while watching the chord chart and melody playback in real-time. If you like the interface, our directory has over 47,000 songs, and it’s always growing!

Learn more: Hooktheory offers numerous free resources. Explore them all in our comprehensive guide.

Tritone substitution in jazz chords (Jobim)

Antonios Carlos Jobim’s Girl From Ipanema is one of those jazz standards that never seems to fade from popular culture. It’s still easily recognized by most people today, even if they don’t know the name. It’s a famous Bossa Nova tune that’s been featured in countless popular works.

The chord progression and melody have a relaxed but melancholic sentiment, reflected by the lyrical theme of unrequited love. Jobim uses a tritone substitution to evoke the character’s sense of tension and pain as he’s ignored by the girl he longs for.

Have a listen to the embedded audio above and take a close look at the chord progression used during the turnaround. It’s in the key of D♭ major, and yet we find a E𝄫⁷ chord (♭II⁷) where the A♭⁷ chord (V⁷) would normally be.

Tritone substitution in classic rock (The Beatles)

It’s less common to hear dominant 7th tritone substitution in pop music. Songwriters using the flat-two chord are more likely to use a simple triad or even add a major seven on top. Purists might say this ♭II chord is not a true tritone sub because it lacks the dominant 7 extension. Nevertheless, the ii → ♭II → I progression follows the most important rule by moving the root note V down by a tritone.

We mentioned Paul McCartney at the beginning of this article. As it so happens, The Beatles used tritone chord substitution on several songs, including I want you (She’s so heavy) and If I fell. Both of these tunes were technically written by John Lennon rather than McCartney, but that’s okay. Let’s have a look at them below and think about what sets them apart.

The intro to If I Fell plays with a common ii → V → I → vi progression, using a tritone substitution to turn the dominant V chord into a flat II chord. Instead of a dominant chord, the ♭II is a major triad.

One of the remarkable tricks with this song happens just after the intro, as the song modulates up a half step from D♭ major to D major. This is an unusual decision because D major was the tritone substitution, and it was acting as a passing chord.

Sonically, this means that the one chord that “didn’t belong” to the key was transformed into the new center of gravity. Lennon pulls this off skillfully using a ii → V → I in the key of D Major immediately following the tritone subbed D major passing chord. Sneaky but effective!

This second example from the Beatles, I Want You (She’s So Heavy), offers a different take on what we’ve seen so far. It’s written in a minor key. Have a listen and watch the chord and melody playback here.

We can pick out several unusual decisions made by Lennon here in the verse. Technically, when a V chord is built from the natural minor key, it’s also a minor chord. In the key of A Minor, the v chord is supposed to be comprised of the notes E-G-B. That’s a minor triad, songwriters will often swap in a major chord instead to create stronger momentum back to the tonic.

That E⁷ chord heard at the end of the verse is an example of this technique, but have a look at the chord that came immediately before it. This B♭⁷ functions as an ♭II⁷ chord, subbing in for the E⁷ momentarily before moving up to the expected V⁷.

Notice also that the V⁷ has a ♭⁹ chord extension, meaning that it’s spelled E-G♯-B-D-F. That F comes directly from the tritone sub that preceded it, where it functioned as the 5th of the chord’s root note (B♭ – D – F).

So whether or not The Beatles “knew” what they were doing theoretically, we have two clear examples already that they could successfully implement chord substitution creatively in their songwriting. These tricks set their songs apart from other more conventional songwriters.

Tritone Sub in mainstream pop (Britney Spears)

Jumping forward about half a decade, we find the same technique in mainstream pop music. The chorus to Britney Spears’ Toxic sounds nothing like jazz but it skillfully employs some complex voice leading with descending dominant chords.

Have a listen here and see if you can spot the tritone substitution.

We’re in the key of C Minor this time, but each of the chords that follow the i chord is dominant. This chord progression is swimming in tritone substitutions and is best understood as a chain of secondary dominants.

A secondary dominant chord takes on the role of a dominant 7th chord relative to a diatonic chord other than the tonic. In other words, where an ordinary dominant chord progression resolves to the i chord, a secondary dominant is set up to resolve to the ii chord, iii chord, or any scale degree other than the root note of the home key.

The tricky part here is that a secondary dominant doesn’t have to actually resolve to the chord that it’s set up against. It can be deceptive and shift somewhere else entirely, as we find in the chord progression for Toxic:

- C Minor: Easy enough, this is the home key.

- E♭⁷: This is a tritone substitution on a secondary dominant of the ii chord (V⁷ / ii). Let’s break that down further in case your head is spinning.

- The second scale degree in C Minor is a D note

- The dominant 7th chord relative to D would be an A⁷

- The tritone substitution for A⁷ is E♭⁷ (that’s the chord featured here)

- D⁷: Sure enough, the tritone sub resolve down to the second scale degree, but with a twist

- The second chord in a minor key is not usually a dominant 7th chord

- This D⁷ is what’s called a V⁷/V, or a secondary dominant of the actual dominant

- D♭⁷: This is the same trick we saw on the E♭⁷ chord. It’s a tritone sub on actual dominant

- The fifth scale degree in C Minor is a G note

- As mentioned before, in a minor key, the fifth scale degree is ordinarily a minor key

- The songwriter did what most jazz and blues artists do, transforming it into a G⁷ chord

- They used D♭⁷ as a tritone substitution in place of the G⁷ chord

- C minor: The tritone sub creates smooth voice leading for the descending bass line back to the home key

The second time through, we get to hear the G⁷ for a moment before it jumps down by a tritone interval, back to the D♭⁷ chord for one last hurrah.

Try playing this on an instrument, and it will feel less complex than if you’re only reading the logic. As I mentioned at the beginning of this article – theory on its own is not enough!

Tritone substitutions in Indie Folk Rock (Mitski)

Even modern indie rock songwriters have been known to use tritone subs in new and unusual ways. Whether they’re thinking about music theory or simply throwing in a weird chord is difficult to know, but it makes more interesting material either way!

This 2014 song Last Words of A Shooting Star by the artist Mitski uses an ordinary ♭II triad chord without the dominant 7th extension. We’re in the key of D major as TheoryTab shows above.

Instead of resolving down to the i chord, Mitski leads us from a secondary dominant (E major: V/V) to a tritone sub on the dominant chord (E♭ major instead of B major), and then jumps up to the IV chord (G major). This allows her to continue the chorus and delay the gratification of hearing the tonic.

Her melody during the tritone sub remains in the home key of D Major, creating a bitonal relationship that’s incredibly tense. So although it doesn’t resolve down to the tonic, the IV chord still comes as a relief for the listener.

Tritone substitutions in K-Pop (Lovelyz)

K-Pop is known for its abundant use of rich, complex chord changes. We’re going to have a look at one more song here, called Shooting Star by the K-pop group Lovelyz, and narrow our focus to a small three-chord excerpt from a pre-chorus. Have a listen to it here.

The tritone substitution we’re looking for is in the descending line from em⁷ → E♭ → dm. It elegantly combines several of the techniques we’ve seen so far. Here’s the breakdown:

- We’re in the key of A Minor, so the Em⁷ is the natural v chord in that home key

- The E♭ major chord is a tritone sub on the secondary dominant leading to the iv chord. Let’s break that down so it’s less confusing.

- The iv chord is dm⁷

- The secondary dominant (V/iv chord) would have been A⁷

- The tritone sub replaces A⁷ with E♭ and omits the dominant 7th extension

- The dm⁷ chord validates the tritone / secondary dominant role of the E♭ chord

If you’re still following along, then you’re probably beginning to grasp some of the main tricks that composers have used throughout history and around the world.

Final thoughts on the universality of chord substitutions

From the jazzy Brazilian flavors of bossa nova, to the British invasion of the Beatles, the toxic American pop of Britney, and the latest trends in K-pop music, we’ve shown you that the tritone substitution has been employed universally by songwriters of all backgrounds.

To summarize, the most common tricks you’ll find are:

- Replacing a V⁷ chord with a ♭II⁷ chord

- Replacing a secondary dominant, like V/V, with a tritone sub like ♭II/V

- The use of tritone subs to create a smooth voice leading down to either the tonic or the target of the secondary dominant

- The deliberate lack of resolution to that target, in favor of an unexpected chord like the IV

There’s a whole wide world of chord substitutions, and this article has only begun to scratch the surface. See if you can begin writing chords and melodies of your own using the technique.

For more examples from popular music, check out our free web app TheoryTab. You don’t have to sign up for an account to search through songs and study them. Our community has notated over 47,000 songs in the database, and it grows every year thanks to people like you!

Learn more: Explore new ways to spark creativity with our Trends tool.

If you liked this overview and want to go deeper, you can also check out our free and advanced chord progression trend database. We analyzed every song in our collection, so you can let us know what chord progression you’re exploring, and we’ll show you all the songs that use it!

Visit https://www.hooktheory.com/theorytab to get started for free today!

About the Author

Ezra Sandzer-Bell is a musician and copywriter with a passion for merging music theory with technology. Learn more about his musical journey and the philosophy behind his work here.