This article is Part 3 of a multipart series looking at the statistics gathered from 1300 choruses, verses, etc. of popular songs to discover the answer to some interesting questions about how popular music is structured. Click here to read Part 1.

In this article, we’ll continue our exploration into the patterns evident in the chords and melody of popular music. First we will look at the relative popularity of different inversions (e.g. a C/E chord vs. G/B, etc.) based on the frequency that they appear in chord progressions found in the Hooktheory Analysis Database. Then we will take a statistical look at how inversions are most often used. For example, if an inverted chord is found in a song, what can we say about the probability for what the next chord will be that comes after it? This will be compared with how the non-inverted counterpart of the chord is used (e.g. a C/E vs. a C).

Inverted chords

When a song is using a C major chord, the lowest note (often played by the bass player if there is one) is usually a C. Sometimes this is not the case, however, and one of the other notes that make up the C major chord will be played instead (the E, or G). These so-called inverted chords occur frequently in popular music. Guitarists reading tablature will recognize them as “slash chords” (i.e. C/E) where the note below the slash is the new bass note.

The popularity of inversions of C and G

Any chord can be inverted, but in practice it turns out only a few are commonly used in popular music. Amongst songs that had inversions in them, the following plot shows the rate at which different inverted chords show up in the database. All songs were transposed to the key of C to make comparison between songs in different keys valid.

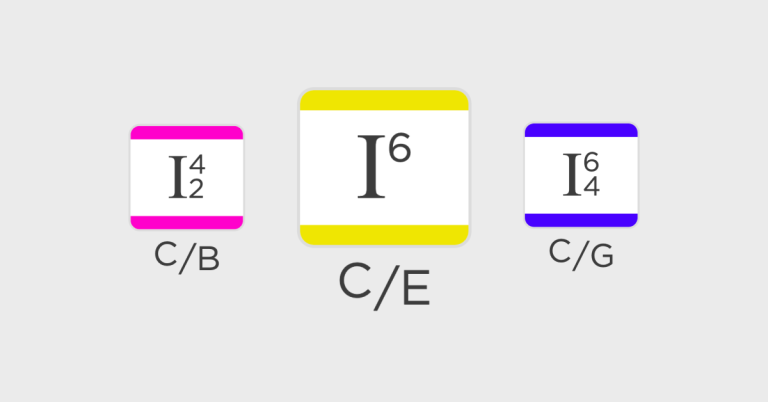

The plot shows that C/E and G/B chords (I6 and V6 in Roman Numeral notation) are the most common by far. Part of this can be explained by the fact that, as we learned in Part 1, I and V chords are very popular chords in general. Yet we also learned that IV and vi chords are almost as popular, and inversions of these chords show up much less frequently than you might expect.

Perhaps a more interesting question to ask is, given that C/E and G/B (I6 and V6) are so popular, how are these chords used relative to their non-inverted vanilla C and G chords? In other words, how does changing the bass note of the chord change how the chord functions?

This question is readily answerable with empirical data from the Hooktheory database.

The usage of C/E vs. C

Let’s start by comparing C/E and C. The following plot below shows the probabilities for what the next chord in the chord progression will be after each chord. The first plot shows the probability for the chord coming after a vanilla C (I) chord. The second plot shows how the probability changes when this chord is instead a C/E (I6) chord.

The most common chords to follow a vanilla C (I) chord are unsurprisingly G (V) and F (IV) (occurring 26% and 46% of the time respectively). The tendencies change dramatically for C/E, however, with F (IV) being by far the most common chord and Dm (ii) gaining quite a bit of ground. Dm is almost 3 times more likely to come after a C/E chord as compared to a vanilla C chord (23% vs. 8%).

These statistics reveal an important function of inverted chords. Inversions are often used to link the bass notes between neighboring chords. In this case the E in the bass of C/E is a neighbor to the D and F in the bass of Dm and F respectively. This is very much in line with what a classically trained musician would expect, but it’s interesting to see these chords used in this way given that many popular songs are composed by people without classical backgrounds. The reason this is such a powerful technique is that our ears hear the lowest note in a song very strongly. It is perhaps less strong than the top note which is why melodies are so important, but the bass note is definitely critical (bass players can take solace in this fact).

A great example of a song that uses the I6 in this way is the intro of Michael Jackson’s Man in the Mirror. The song floats between ii (Dm) and IV (F) using I6 before finishing in textbook fashion with IV → V → I.

The usage of G/B vs. G

We find a similar story for G/B (V6). The following plot shows the probabilities for what the next chord in the chord progression will be after each chord. As before, the first plot shows the probability for the chord coming after a vanilla G (V) chord. The second plot shows how the probability changes when this chord is instead a G/B (V6) chord.

The plot shows that vanilla G (V) chords normally split almost evenly between going to C, F, and Am (I, IV, vi) (32%, 25%, and 29% respectively). Again since these are the most common chords, this should be not be all that surprising. However, the data clearly show that this is no longer the case for G/B (V6). Going to the vi doubles in popularity (from 29% to 61%) to become far and away the most popular transition. F (IV) takes a big hit, occurring 2.5 times less frequently, while C (I) holds more or less steady. Why does G/B to Am seem to occur so much more than G to Am? It’s likely for the same reason that C/E likes to go to F and D so much. Linking up neighboring bass notes creates a nice effect that clearly is a very common technique in popular music.

A good example of a song in the database that uses G/B like this is the Rolling Stone’s “Beast of Burden”:

Here are some other examples in the Song Database that do this too:

“Your Song” by Elton John is a song that does something uncommon after G/B. It goes to the iii (Em). Aside from this departure, Elton tends to use chords in a very typical fashion (though he’s uses every trick in the book to get the sound he wants).

Though he doesn’t use the V6 to create a linked bass line here, he uses inversions of 7 chords (vi42) and secondary dominants (vii˚7/V, oh my!) to connect the vanilla vi chord by step with the IV to complete the progression (the bass note goes A → G → F# → F. We’ll talk about how songwriters like Elton use these more complex harmonies in future posts.

What’s your favorite use of inverted chords in a pop song? Are they used in a way consistent with these findings? Let us know in the comments below.

Other posts in the 1300 song series

- Part 1: I analyzed the chords of 1300 popular songs for patterns. This is what I found.

- Part 2: I analyzed the chords of 1300 popular songs for patterns. This is what I found.

- Part 3: A statistical study of inversions (slash chords) in popular music.