It’s fun to learn jazz chord progressions, even when the process feels a bit challenging.

We all need to start somewhere. Whether you’re self taught or enrolled in a program, you’ve got to take things from square one and build up slowly.

Music schools typically combine music theory with instrument lessons to make sure the concepts are anchored in physical understanding. Students are encouraged to practice improvisation with simple scales and arpeggios before building up to solos and jazz standards.

In this article we’ll be focusing on learning chord progressions specifically, with links to free tutorials from jazz musicians and educators from around the world. We’ve also published music theory books that you can reference at any time, to work on your fundamentals.

We’ve found that it’s easier to grasp these ideas when you can see and interact with them. That’s why we’ve embedded examples from TheoryTab. Instead of simply reading about the concepts, you’ll be able to pick up your instrument and play along!

Chord charts and Roman numeral notation

Jazz musicians generally use chord charts in place of traditional notation. The shorthand approach leaves chord voicings open to interpretation and allows for more flexibility during improvisation. Here’s an example of what a chord and melody chart often looks like:

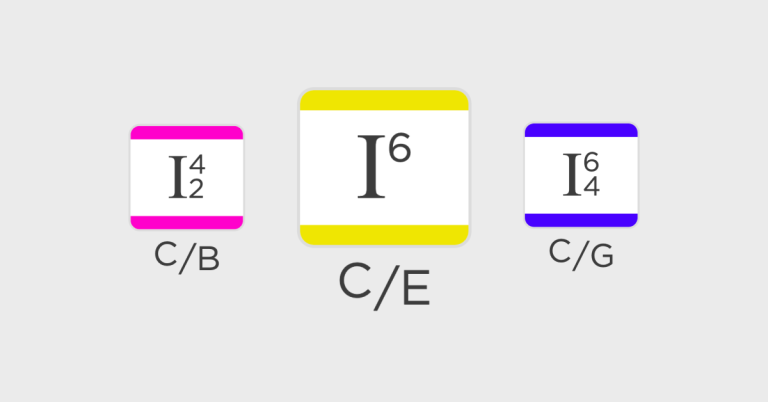

Roman numeral notation is different from what you see above. It exists at a layer of abstraction above the actual chords. It’s used to analyze harmonic structures that could be applied to any key. In this way, it doesn’t dictate the precise chords that you have to play.

The example below shows how the seven diatonic chords are notated in major and minor keys.

Capital letters are used to indicate a major triad, whereas lowercase letters indicate a minor triad. The i chord in a minor key is lowercase, while a I chord in a major key is capitalized. The same is true for the letter v.

It’s common to find Arabic numerals (sus4, add6, 7, 9, 11, 13) written in superscript at the upper right corner of a Roman numeral. These numerals represent chord extensions or color tones that build upon the fundamental triad.

The most common jazz chord progressions

Jazz chord progressions have a few qualities that set them apart from other popular genres.

Rock chords were historically built around triads without chord extensions. Punk rock stripped this down further, using power chords (perfect fifth intervals) with no third.

In more recent history, Trap music began avoiding chord progressions in favor of melodies built on the Phrygian mode and other “dark” scales. They focus on percussion instead of chords.

When people play jazz, they use colorful chord extensions that set it apart from other genres. When those chords find their way into old-school hip-hop, pop music, and K-pop, musicians often refer to them as “jazzy.”

In the following sections, we’ll outline the most important jazz progressions to know about.

The ii → V →I Progression

The ii → V → I progression, pronounced “two five one,” is arguably the most common in all of jazz. You will see in a moment why the abstraction is helpful, because it’s key signature agnostic.

In the Key of C Major, this progression takes the form of Dm⁷ → G⁷ → Cmaj⁷. But in the Key of G Major, the same progression is expressed through different chords: Am⁷ → D⁷ → GMaj⁷.

It’s just as common to hear the ii → V → I progression in a minor key.

For example, in the Key of C Minor you get the chords Dø⁷ → G⁷ → Cm⁷. That funny looking circle with a slash through it is called a half diminished seventh chord. It occurs naturally on the second scale degree of a minor key, rises up to a dominant chord, and resolves to a minor chord.

“Autumn Leaves“

The following jazz song, “Autumn Leaves,” is a prime example of the minor ii → V → i progression. We’ve embedded an example from TheoryTab below. Find the chord symbols under the MIDI melody notation.

Can you spot the minor ii → V → i in this progression?

What we’re seeing here is a rotation through each diatonic chord in the scale, by way of the circle of fifths in the chords’ root notes.

Let’s start with the first three chords in the sequence: Gm⁷ → C⁷ → Fmaj⁷.

On the surface, this looks a ii → V → I in the Key of F Major. But we are in the Key of D Minor, and the cycle continues past the F major chord. As we continue listening and reading the chart, we find that the F chord is functioning as a III chord, moving through a III → VI → ii → V sequence before resolving down to the i chord, D minor.

Rhythm Changes

A second example, called the “Rhythm Changes” progression, comes from the George Gershwin tune “I Got Rhythm.” This one is in a major key instead of a minor key. It begins with a i → vi → ii → V sequence in the A section and is followed by a iii → VI → ii → V → I in the B section. The same progression is found in other popular jazz standards like the Sonny Rollins tune “Olio.”

Explore jazz standards based on the ii → V → I progression

Want to go deeper and see how this ii → V → I progression has been used by other artists? We’ve assembled a list of jazz standards from the TheoryTab database for you to study.

- Cole Porter – “Anything Goes” features a ii → V →I in the Key of B♭ Major

- Nat King Cole – “L-O-V-E” is a classic jazz standard in G Major that seesaws between the ii and V chords before resolving to the I chord.

- Charlie Parker – “Yardbird” features a deceptive ii → V → iii sequence that later returns to an actual ii → V → I in C Major

- Count Basie – “Hay Burner” uses a deceptive cadence. The ii → V → vi sequence tricks the listener into thinking that they’re about to hear a resolution to the tonic, but moves to the vi chord instead.

- Chick Corea – “Spain” is in B Minor and has a iiø⁷ → V⁷ → Isus4 at the end of the phrase.

- Casiopea – “Galactic Funk” opens with a ii → V → i in E Minor before spinning off into uncharted territory. This subverts the usual role of ii → V → i as marking the end of a phrase.

Jazz blues progressions

The blues was an early predecessor to jazz. Instead of using the ii chord, blues musicians used the IV chord. One of the most common blues progressions is the I⁷ → IV⁷ → I⁷ → V⁷ sequence, where each triad is turned into a dominant seventh chord.

Here’s an example of a 12-bar blues from the artist Bessie Smith:

In the Key of E Major, we end up with an E⁷ → A⁷ → E⁷ → B⁷ progression. Traditional Blues music tends to resolve the IV chord down to the root chord before going back up to the dominant chord.

Jazz musicians embellish this basic blues progression with more elaborate chords and substitutions. However, if you see tunes that built dominant chords around something other than the V chord, it’s safe to bet that this was inspired by the Blues.

Etta James – “Something’s Got a Hold On Me” is another textbook blues tune in the unusual Key of C♯ Major. The song mostly moves between the I and IV chord, but the pre-chorus has a I → V → I → IV progression.

Modal jazz progressions

Modal jazz is characterized by modes (such as Dorian, Mixolydian, and Lydian scales) rather than traditional functional harmony. They use static harmony that vamps around one or two chords, with most of the novel material located in the melody.

For example, the Miles Davis tune “So What” is based on a Dorian mode, comping between two chords: Em¹¹ and Dm¹¹. The E minor acts as a passing chord down to the Dorian root. We can hear the iconic minor scale melody located in the bass line.

Listen to the full track, and you’ll hear an example of chord modulation from the band as they shift up to a new tonal center. This is a common way to refresh the ear without necessarily changing other core elements like the rhythm or lead melody. It’s a common trick in modal jazz.

Freddie Hubbard’s “Little Sunflower” is a second example of modal jazz and interestingly enough, it also vamps on D Dorian. Notice how the bridge modulates up a half step to E♭ minor and repeats the same concept.

Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage” is a third popular tune in the modal jazz tradition. Believe it or not, this song also is in the Key of D Dorian. In case you think that this is some kind of hard and fast rule, it’s not. Hancock has other modal tunes, like “Chameleon” in B♭ Dorian.

Bebop: Advanced jazz chord progressions

Bebop was a high-octane style of jazz that emerged during the 1940s. It features complex harmonies at fast tempos and switches to different keys mid-song without any reservation. Charlie Parker and John Coltrane were two of the most famous artists from this era.

Giant Steps features one of the most common jazz chord progressions found in bebop. It’s highly advanced in some ways, but once you get the core idea, the most difficult part about it is learning how to play the chords!

Sometimes called the Coltrane progression, this tune leverages the more common II → V → I progression while cycling through a series of key centers by descending major thirds.

Have a listen below, and then we’ll break down what’s going on.

We begin in the Key of B Major. It feels almost like John is playing a practical joke, because the key center lasts for a single chord before shifting down by a major third to the Key of G Major. The V⁷ → I⁷ relationship of D⁷ to G⁷ lasts for two chords before shifting down again, this time to E♭ major.

One of the most interesting details about this jazz chord progression is the symmetry. Notice in the diagram above that the notes B, G, and E♭ form a perfect triangle when mapped onto the chromatic circle. Coltrane did this deliberately and wrote about musical geometry in great detail.

Symmetry can also be found in the four notes of a fully diminished chord, forming a perfect square, and the whole tone scale that forms a hexagon. We’ll get into that next in our section on chord substitutions.

For a deep dive on the jazz theory behind Giant Steps and bebop in general, check out this article from the Jazz Modes blog.

Advanced chord substitutions

Chord substitutions are an advanced technique that jazz guitarists and pianists use to re-harmonize melodies. We’ll cover a few of the most common techniques now.

Tritone substitutions are perhaps the most common trick in the book. We wrote about them extensively in this article and broke down precisely how they work. In a nutshell, you can take a 7th chord and move the root down by six semitones to create a new chord that plays nicely with the original melody.

Jazz music has come a long way since the blues, swing and even bebop. The harmonic framework of these early 20th century genres have continued to define the way jazz guitarists and pianists approach their chord voicings and compositions.

Here’s a collection of Jazz songs that feature interesting chord substitutions:

- Anomalie – “Metropolie” came out only a few years ago and is a shining example of how complex jazz theory has become. It overflows with borrowed chords and there’s no ii → V → I in sight, despite being firmly in the modern jazz genre.

- Jacob Collier – “All I Need” is another advanced jazz tune with pop sensibilities. It bounces between the minor and major tonic, with rapid passing chords at the end of each bar.

- Vulfpeck – “Animal Spirits” uses secondary dominants and unusual chord sequences to keep the listener on their toes.

- Snarky Puppy – “Outlier” blurs the lines between jazz and progressive rock in this tune, where more than half of the chords in the progression are borrowed from another key.

Check out our article on cinematic chords in film music to study how some of the great composers have defied conventions to evoke intense emotional states in their audiences.

We hope you’ve found this article enjoyable and learned something new in the process about jazz chord progressions. Check out the TheoryTab database to explore nearly 50,000 songs across every genre.

About the Author

Ezra Sandzer-Bell is a musician and copywriter with a passion for merging music theory with technology. Learn more about his musical journey and the philosophy behind his work here.