Counterpoint is an advanced concept in Western music theory dating back to the 16th-century Renaissance. It evolved into “tonal counterpoint” during the Baroque period and has remained relevant in some popular genres of music to this day.

Strip away the rules enforced by university professors, and you’ll find that counterpoint music amounts to two or more independent musical lines being played simultaneously. It’s a framework that favors a view of music as layered, horizontal melodies rather than rhythmic, vertically stacked chord shapes.

It comes down to a distinction between vertical harmony and independent horizontal melodies.

Most studio musicians replace the word counterpoint with casual language like “guitar and bass riffs that work well together” or “vocal melodies and countermelodies.” You’re not likely to hear phrases like “contrapuntal composition” outside the halls of academia.

Songwriters take a vertical approach to chord harmony and write a single melody for the lead. It’s up to the band to figure out how to translate those chords into horizontal lines. That’s very different from the classical composer, who took full control over every instrumental line.

Today’s chord charts allow for quick and easy communication between session musicians. The vertical stacks are a blueprint that each player can reference. It’s up to the individual to decide how to articulate those notes, whether with syncopated finger-style picking patterns on a guitar or arpeggiated chord shapes on the keyboard.

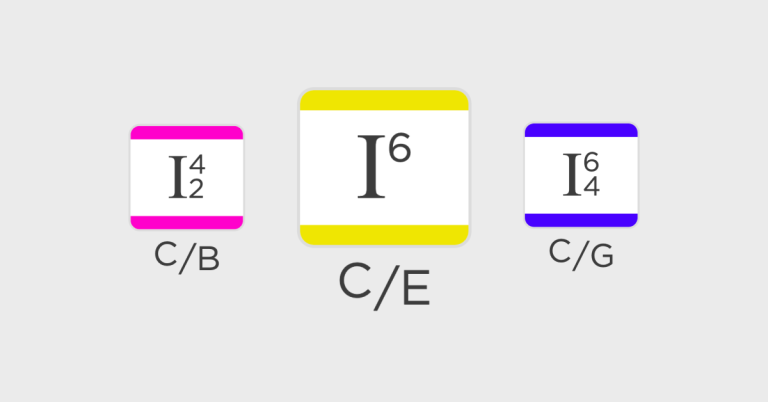

Monophonic (single note) instrument layers, like a bass line, aim for notes that support the chord without re-contextualizing it. As the lowest frequency, they can change the way all of the upper register voices are perceived. Therefore, they often play the root, third, or fifth on the downbeats unless the chord explicitly calls for a colorful bass note. The other scale degrees are permitted on weak beats and that’s now melodic, horizontal bass lines are written.

Ultimately, the art of counterpoint is about skillfully unpacking basic chord progressions into complex multi-instrumental lines. Many rules were set up during the 1600s-1900s that defined how to approach these weaving, interlocking melodic layers. Some of them still hold true today.

Imitative counterpoint: Rounds and fugues

The round is a simple type of imitative counterpoint found in children’s songs. Songs like “Row Row Row Your Boat” or “Frère Jacques” consist of a single melody performed by four voices. Each voice imitates the last through direct mimicry.

When the first voice completes a measure, the next voice comes in with that same melodic line. The pattern continues one voice at a time, and the group keeps singing until someone decides they’ve had enough!

Here are the basic elements that make up a round:

- Imitative counterpoint: Each voice enters at a different time, imitating the melody of the previous voice. Some variations could be introduced, or in examples above, like “Row Your Boat,” each voice sings precisely the same melodic line.

- Independence: Although each voice sings the same melody, they do so independently, creating harmonic and rhythmic interplay. You could say the whole round becomes greater than the sum of its parts.

- Repetition: The melody is repeated in each voice, leading to a cyclical and continuous musical structure. That’s why it’s called a round and the main factor that differentiates it from other types of counterpoint.

Fugues are a more advanced form of imitative counterpoint in which patterns respond to one another from different scale degrees. For example, a given shape might be repeated by a second voice but four notes down within the scale.

The TheoryTab audio player above features J S Bach’s famous “Fugue in C Major.” We’ve annotated an image below to show the fugue’s imitative counterpoint in a MIDI piano roll layout. The first orange melodic line begins on C natural. As it progresses, the green melodic line enters with a similar shape, beginning with G natural. The tail end of the first melody is juxtaposed with the reiteration of Bach’s motif in a new pitch register. This happens again with the third voice.

Counterpoint in 20th and 21st century pop music

Not sure what 18th-century fugues have to do with your life in the 21st century? In this next section, we’ll show you how psychedelic pop bands from the 1960s and 70s revived some of these techniques and inspired decades of music that followed.

Beach Boys, Beatles, Simon & Garfunkle

“God Only Knows” is a famous example of vocal counterpoint found on The Beach Boys album Pet Sounds. Have a listen with the embedded TheoryTab player below and focus on the interplay of the voices:

The song’s outro features several people in the band singing the phrase “God only knows” in different pitch registers, much like Bach’s fugues. Lead songwriter Brian Wilson used this technique frequently on the album and later tracks like “Our Prayer.”

Paul Simon was also fond of writing independent melodic lines in his early works with Simon & Garfunkle. He used a harpsichord in the arrangement and heavy reverb to draw the listener back in time, with Baroque counterpoint techniques in the harmony.

This song, “Because” by The Beatles, offers another good example of popular counterpoint music. Instead of the choral fugues heard from The Beach Boys, the vocal harmony moves in parallel motion.

Notice how the lead vocal melody stretches up and back down in stepwise motion on the diminished ii7 chord. That contrary movement in the upper voice, against the other sustained vocals, brings the song closer to counterpoint.

Radiohead: “Paranoid Android”

Decades later, Radiohead took a stab at their own psychedelic counterpoint on the track “Paranoid Android” from the album OK Computer. We hear a dramatic fugue set up first with open vowel tones during the bridge. As Thom Yorke’s lead melody comes in on the second round, his cryptic lyrics interact with the established harmony.

On the third pass, a few voices come in on a synthesizer and vocally. The passion and emotional intensity are enough to make your spine tingle!

Animal Collective: “Leaf House”

Animal Collective took a more lighthearted approach to vocal counterpoint in their track “Leaf House” from the 2004 album Sung Tongs. They layered several independent voices, ranging from punctuated and repeating vowels to hill-shaped lead melodies in stepwise motion.

Even the final moment in this section — where the voices sing a call and responses between “Me-oo-ow” and the dissonant response “Kitties” — can be viewed through the lens of contrapuntal music. The silliness of this track falls way outside the conventions of classical music forms, but it’s a fitting example of how the technique has changed in modern Western Music.

James Blake: “Life is Not The Same”

Even in the past few years, experimental pop artists like James Blake have employed vocal counterpoint for dramatic effect. This track, “Life is Not the Same,” features harmony in parallel motion. As they sustain over the third and fourth chords, we hear a squeaky contrapuntal melodic line in the upper voice, filling the space and keeping the song’s momentum.

Like the prior example of “Because” by The Beatles, this brief moment of counterpoint is far from being a fugue. Still, it evokes the idea of contrary motion in an independent voice, if only for a single measure.

Traditional Counterpoint Music

Now that we’ve had some fun exploring modern music, it’s time to trace our way back to the origins of the technique.

One of the most influential counterpoint music theory texts dates back to the early-to-mid 1700s, in a seminal work by Johann Joseph Fux called Gradus ad Parnassum. Fux’s book was based on the 16th century counterpoint of composers like Palestrina. It paved the way for the tonal counterpoint of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Fux defined five methods, or species, of counterpoint. With each new species, the number of notes in the countermelody grows. It’s always built around a cantus firmus, or a main melody, but the techniques for harmonizing change from one species to the next.

The primary melody can be located in the bass line or in an upper voice. What matters is that the notes in the complimentary voice follow a strict set of rules. The music education company Ars Nova offers a complete guide to the rules of polyphonic music in the Baroque period.

First species counterpoint (Note-against-note)

First species counterpoint (Note-against-note) consists of a simple one-to-one relationship between the cantus firmus and the second voice. The composer aims for consonant intervals and practices good voice leading, using stepwise motion instead of jumping around chaotically.

We’ve embedded a famous example above from the fast and furious Bach “Prelude No.2 in C minor.” Bach did not conform strictly to Fux’s model; the composition features note-against-note patterns but features both perfect consonances and imperfect consonances in the voices.

A perfect consonance includes perfect unison, perfect fourth, and perfect fifth intervals.

Imperfect consonances are the indicators of major and minor keys, so the third, sixth, and seventh. The second interval was considered a dissonant interval, so even though it’s not an indicator of the key, it was also not treated as perfect.

Second Species (Two-notes-against-one)

Second Species (Two-notes-against-one) features two notes for every one note in the cantus firmus. For this reason, composers now have to think about passing tones and neighbor tones. Dissonance against the main melody is permitted on the weak beats, as long as they’re properly prepared and resolved.

Third Species (Four-notes-against-one)

Third Species (Four-notes-against-one) continues the pattern, introducing four notes for every one note. This offers more room for rhythmic activity and more advanced use of dissonance.

Fourth Species (Syncopation or Suspended Counterpoint)

Fourth Species (Syncopation or Suspended Counterpoint) displaces the counter melody to create rhythmic syncopation. If the cantus firmus consists of whole notes performed on the first note of each measure, fourth species counterpoint would position a countermelody on the third beat of each measure and sustain it across the first two notes of the next measure. This creates tension with dissonance against the strong beats, resolving to consonance on the weak beats.

Fifth Species (Florid Counterpoint)

Fifth Species (Florid Counterpoint) combines the rules of the previous four, while going deeper into conditions that were permitted during the Baroque period. For example, perfect unison (two melodies playing the same note) was only supposed to occur during the beginning or end of a musical composition or passing as long as it was not an accented beat. Half and quarter-note rests were also common.

Before we wrap up this article, let’s take some of the terminology we’ve just learned and try applying it to popular music. The rules of consonance and dissonance won’t apply, but the note-against-note rhythm guidelines do appear.

Louis Cole – “Everytime” (1st, 2nd, and 3rd series)

We found a great example from the 2018 avant-pop track “Everytime” by songwriter Louis Cole of Knower, and embedded it in the TheoryTab music player below:

The arpeggiated melody in the keyboard voice plays a steady 8th-note rhythm, while Cole’s vocal melody explores a few simple rhythmic variations.

When he sings, “I think it’s gonna be a simple thing,” each syllable is granted one 8th note, just like the synth. This could be seen as a rhythmic correlate to Fux’s first series counterpoint (though not tonally).

The next line, “Think… I’m… way… off…” enunciates a single melody note for each of the four notes in the synth arpeggio. This could be compared to a third species. Finally, his lines “Stop searching” and “Stop learning” feature two notes against one or second series.

It’s important to acknowledge again that Cole does not follow the rules of harmony that Baroque music demanded of its composers. Our modern ears are comfortable with dissonant intervals and musical forms that would have been inappropriate three centuries ago.

Academics who teach counterpoint would probably object to the use of traditional language to describe what Cole is doing. After all, they are from different periods and follow different rules. If you want to truly grasp Renaissance and Baroque counterpoint, you have to study music from that period.

Counterpoint exercises to try on your own

Here’s a counterpoint exercise you can try at home to get a feel for the process of writing horizontally with interdependent melodies. Fair warning — if you’re used to writing around chord progressions, this new approach may take some getting used to!

The technique we’ll be exploring here centers around using a pedal point. This is a repeating note that persists through the other counterpuntal voices in your idea. To demonstrate what that might sound like in practice, let’s have a look at this tune from The Beatles.

In the song “Blackbird,” McCartney uses an open guitar string as a pedal while the other notes move in parallel motion. He plays the stationary note on the off-beat, which helps establish it as an independent melodic line. Each string of the guitar corresponds to its own line, and when his vocals come in, they act as a third horizontal layer in the composition.

Writing counterpoint around a pedal tone

Pick a note that will act as your pedal tone on your instrument of choice and begin by repeating it with a quarter-note pulse. Now, write a second voice, also with quarter notes, that moves in stepwise motion up or down away from the pedal.

Once you’ve got a counter melody, add a bass note that plays whole or half-note durations.

It’s important to have the discipline to think in horizontal rather than vertical forms. Look at the bass notes as independent voices rather than root notes of a chord. You can analyze the chord forms later if you want to, but that’s not part of the first step.

Finally, sing some lyrics or vocal tones that accompany these three melodic lines. You can do this intuitively, with whatever rhythm you want. If you’re not sure what to sing, try using imitative counterpoint. That means your singing voice can repeat ideas from the instrument melodies as long as they’re not moving in unison.

Just like that, you’ve got four independent voices woven together. Don’t be afraid to listen to J S Bach for examples of voice leading and “tonal counterpoint.” The rules of music have changed a lot over the past few centuries, but you still might get ideas for rhythm and phrasing to use as a starting point.

We’ll close out with Air on the G String, one of the most famous and beautiful pieces by Bach. Explore our full collection of more than 50,000 songs and musical compositions at TheoryTab.

About the Author

Ezra Sandzer-Bell is a musician and copywriter with a passion for merging music theory with technology. Learn more about his musical journey and the philosophy behind his work here.